In Gratitude To The Missionaries Who Carried Out Humanitarian Missions During The Armenian Genocide

CULTURE

18.12.2024 | 21:16

“Our silence and inaction make us complicit in crimes committed against humanity.” Johannes Lepsius

In Soviet historiography, the German missionaries active during and prior to the Armenian Genocide, which began in 1915, were predominantly portrayed—apart from a few exceptions—as engaging in espionage and hostile activities. Simultaneously, numerous archival documents attested to the missionaries’ humanitarian role and their selfless efforts. Against this backdrop of contrasting contradictions, the pursuit of truth played a significant role in Hayk’s life. With each new book and archival document he encountered, he uncovered new missionaries, unknown even to his colleagues within the academic community. Thus, Hayk’s first workplace was the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, where his knowledge of languages propelled him to uncover new and remarkable episodes from the histories of Armenia, the Ottoman Empire, Germany, and the lives of numerous individuals whose stories future generations ought to know.

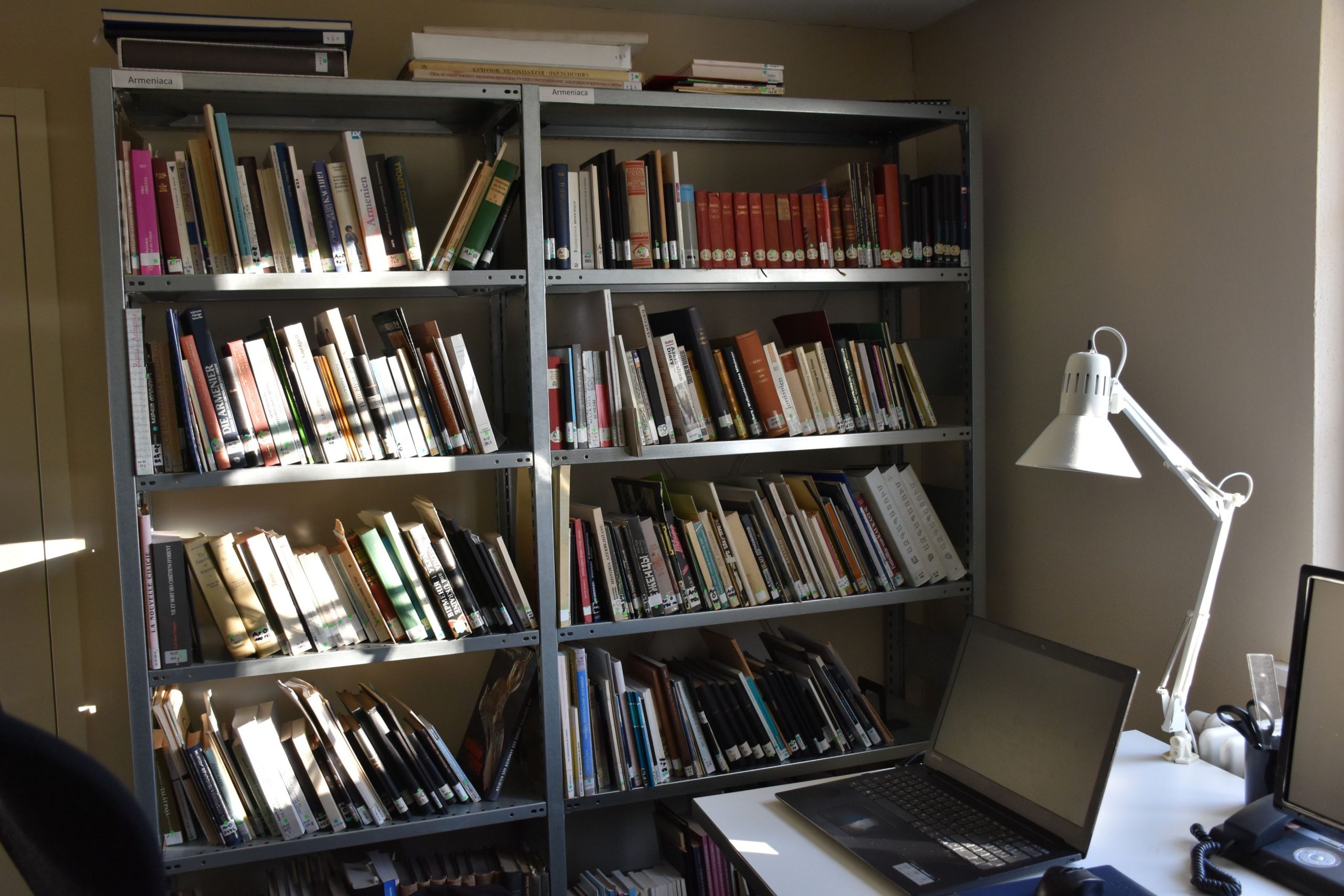

Currently, Hayk Martirosyan is one of the researchers at Lepsiushaus.

Hayk Martirosyan at the Lepsiushaus archive, Potsdam, October 2024.

The Lepsiushaus was established at the location where Johannes Lepsius lived from 1908 to 1926. It is here that one of his significant works was published—the 1916 book later known as The Armenian People’s Death March. The legacy of Lepsius’s commitment, as well as his partially ruined house, which was used by the Soviet army as a cash office after World War II until the early 1990s, was in danger of being forgotten. In March 1999, as a result of the union of residents, church representatives, scholars, and socially concerned individuals, the Lepsiushaus Potsdam Support Association was established. This association initiated the restoration of Lepsius’s house and made its dignified preservation a central mission. Professor Hermann Goltz, a founding member and long-time member of the association’s board, played a significant role in this effort.

Johannes Lepsius’s study room, Lepsiushaus, Potsdam, October 2024.

In 2005, on the 90th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, the Bundestag adopted a resolution explicitly condemning the persecution and massacres of Armenians during World War I. The resolution also acknowledged Germany’s shared responsibility, stating: “Germany, which contributed to the realization of the crimes committed against the Armenian people, must also take responsibility.” At the same time, the Bundestag decided to honor the life and work of Johannes Lepsius. The restoration of the Lepsiushaus began in 2008. In May 2011, it opened its doors to the public as a research center for genocide studies. In December 2010, Goltz passed away and did not live to see the opening of the LepsiusHaus. After the opening, the directorship was taken over by one of Goltz’s students, Dr. Rolf Hosfeld, who managed it until the summer of 2022. The directorship is now held by Dr. Roy Knocke.

Lepsiushaus Archive, Potsdam, October 2024.

In 2015, a memorial stone commemorating the centenary of the Armenian Genocide was placed in the courtyard of the Lepsiushaus. The cross depicted on the back of the stone was blessed by a bishop of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Inscribed on it in Armenian and German are the words: “Լուսաւորեա Տէր զհոգին Ծառայից քոյ” (Lord, illuminate the soul of Your servant).

The Armenian Genocide Centennial Memorial Stone in the courtyard of the Lepsiushaus, Potsdam, October 2024.

In the photo: journalists Stella Mehrabekyan, Alexander Martirosyan, and Sofi Tovmasyan on the left; and Heriknaz Harutyunyan and Frunze Avetisyan on the right.

Hayk began his academic work in Germany at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg in Bavaria. Since 2011, German academic exchange programs and scholarships provided by Catholic and Evangelical churches have regularly given him the opportunity to return to Germany and continue his studies. Thanks to the scholarships, Hayk was able to collect numerous archival documents and information, which provided rich material for his doctoral dissertation. In 2017, Hayk returned to the University of Erlangen, where, after negotiations with his professor and the director of the Lepsiushaus, Rolf Hosfeld, he decided to move to Potsdam, home to the Johannes Lepsius House-Archive. The Lepsius House-Archive was the place where Hayk could continue his academic research while simultaneously contributing to its activities.

His main research topics focused on German missions in the context of the genocide. While Johannes Lepsius’s mission is the most well-known to us, there were five other Evangelical organizations and one Catholic organization in Germany that also carried out significant work. These included efforts in orphan care, education, medicine, and providing financial support to the Armenian Catholic community. Hayk’s main focus of study was these missions, the restoration of the biographies of orphans, and Armenian-German relations from the Hamidian massacres to 1920-21. At the end of 2024, Hayk’s book, Humanism and Christian Compassion: The History of German Missions Among Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1896-1919, will be published. This work, the result of years of research, summarizes the activities of Evangelical and Catholic missions, Lepsius’s extensive work, and his efforts in support of the Armenian cause.

From 2020 to 2022, Hayk taught at Halle University in Germany. This is one of the greatest achievements of his career.

“This long-awaited achievement turned out to be the saddest day for me. My first lecture was on November 10, 2020. I didn’t know how to teach; I hadn’t slept all night and was overwhelmed with countless emotions. The work I had done for years was leading me toward fulfilling my goal. It seemed that the first day of my teaching should have been the happiest, but it turned out to be the most cursed.”

In the past ten years, there have been Armenian Studies professorships in Germany (positions lower than a full academic chair). In 2012, the Armenian Studies professorship at the Free University of Berlin was closed. At the end of 2022, the professorship in Halle, which had been established in 1998 through the efforts of the Armenian government, was also closed. Interestingly, in places where Armenian Studies professorships are being closed, there has been a sharp increase in Azerbaijani academic influence. While there is no direct connection between these patterns, such coincidences give rise to speculation. Some Armenian and pro-Armenian professors have retired. In this context, Hayk raises very important questions for Armenia and the Armenian government:

“How will the gap in Armenian Studies in Germany be filled? Do we want to fill that gap or not? Professors have retired, Armenian Studies centers have closed. What is Armenia’s response now—do we want to develop Armenian Studies or not?”

Hayk is very eager to pass on the institutional knowledge he has acquired to younger generations and students in a more sustainable way. This is not only about the work of the Lepsiushaus or the missions of Lepsius and other missionaries but also about the stories of the surviving orphans, the paths they traveled, and the revaluation of their lives.

“Imagine a wealthy family living in Germany, a renowned doctor, or a well-off man or woman who leaves their secure life behind to go to the Ottoman Empire and live among Armenians. I want the stories of these people to become accessible to everyone. I want to find answers to numerous questions: why did they go, how did they decide to go, and what did they witness? In response to their selfless work, 100 years later, I want to express my gratitude on behalf of myself and all of us. Based on the calculations in my research, I can say that at least 250-300 dedicated missionaries were involved in caring for Armenian orphans and saved thousands of lives. I should note that in our professional circles, only 10-12 of them, at most 15, are well-known. For me, it is very important to reconstruct the lives of these individuals, to recognize their self-sacrificing work, and to contribute to the formation of institutional memory about their efforts.”

Hayk recounts that a few years ago, the grave of one of the German missionaries was leveled to the ground. In Germany, it is customary for graves to be removed after a certain period, with new ones established in their place. He asked one of his close friends to collect soil from the missionary’s grave, hoping that one day it would be placed behind the memorial wall of the Armenian Genocide Memorial Complex.

“Gratitude is a good thing; we must remember these people.”

Regarding education, it should be noted that as part of its activities, the Lepsiushaus also provides training for teachers. In Germany, Brandenburg was the first federal state to introduce the topic of the Armenian Genocide in schools (2002-2003). The number of states currently stands at four, and soon there will be a fifth. Hayk notes that education in Germany is of a very high standard. Ninth-grade students who visit the Lepsiushaus stand out for their knowledge, the astonishing depth of their questions, and their emotional intelligence. They deeply empathize with and understand historical realities.

“One time, a schoolboy from Berlin called me and asked to come to Potsdam, to the Lepsiushaus-Archive, on the same day. During a history lesson, he had learned about the Armenian Genocide for the first time and wanted to get information from a primary source. I showed him the rooms of the Lepsiushaus, presented historical episodes, and shared facts about the past. In the end, he admitted that one of his parents was Turkish and the other German. After his visit to Potsdam, he decided that he would write his final school project on this topic.”

Touching on the topic of empathy and generational memory, Hayk mentioned that he is starting another project aimed at understanding how Germans are portrayed in the memories of genocide survivors: their socio-psychological characteristics, as well as positive and negative perceptions. The topic is quite interesting and has not yet been studied, despite the abundance of memoirs on this aspect.

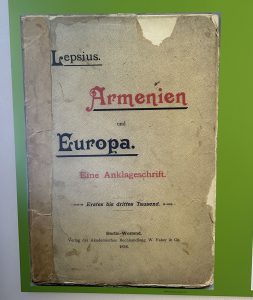

Returning to Lepsius, it is important to highlight that he published three major books about Armenians and the genocide. In 1896, he traveled to the Ottoman Empire for six weeks, and upon his return, he published his famous work, Appeal to the Great Powers and a Call to Christian Germany. In this work, he detailed the massacres, violence, and deportations, spoke about the clergy, and provided extensive statistical data. Before the publication of the appeal, he disseminated these accounts in a German newspaper. Lepsius was one of the first to recognize the significant influence and importance of newspapers and media in lobbying, spreading information, and raising public awareness. Based on these publications, he prepared a book, which was first released in September 1896 and was reprinted seven times within two years.

“For example, it was a revelation for me to discover that during the Hamidian massacres of 1896-97-98, one could find over a hundred press outlets that published daily and weekly news about the massacres carried out by the Ottoman Empire. Such a volume of information was unimaginable for the media operating 120-130 years ago. Even during the 2020-23 Artsakh war and the events of ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of civilians, there weren’t as many media references as there were during the Hamidian massacres. Of course, this awareness was also driven by Christian missions supportive of Armenians. It should also be noted that the reports published at the time included astonishingly detailed and harrowing descriptions of the events.“

The cover of Johannes Lepsius’s 1896 publication, Appeal to the Great Powers and a Call to Christian Germany. Lepsiushaus, October 2024.

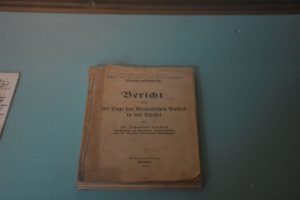

Lepsius’s second book was published in 1916. In 1915, using his connections, he managed to travel to Constantinople and meet with Enver Pasha, with the aim of advocating for the Armenian people—a mission that, unfortunately, yielded no results. During this time, he also held meetings with American and other foreign diplomats to discuss the issue. Lepsius returned from Constantinople with numerous documents and information. In 1915, Germany enacted a censorship law that prohibited any discussion of the genocide. Against this backdrop, Lepsius’s second book, The Armenian People’s Death March, was published. The issue was even raised in the Reichstag (now the Bundestag), but it received no response. In the book, Lepsius criticized the Ottoman Empire, which was an ally of Germany at the time, and provided detailed descriptions of various episodes of the genocide. Since Lepsius had a great passion for mathematics, the book also included ample numerical data and statistics highlighting the scale of the tragedy. The book was published in 20,500 copies, some of which were intended for high-ranking officials and parliamentarians. However, a significant portion never reached its intended recipients because German police confiscated them. This led to the growing risk of being accused of treason and arrested for violating the censorship law and detailing the events taking place in the Ottoman Empire. As a result, Lepsius relocated to The Hague, where he remained until the end of World War I.

Johannes Lepsius’s 1916 publication, Report on the Situation of the Armenian People in Turkey, later renamed The Armenian People’s Death March in its 1919 reissue. Lepsius House, October 2024.

“In modern terminology, Lepsius was a phenomenal lobbyist. He did not seek collaboration with the authorities and instead demonstrated resistance. In the 1920s, when camera production and usage began, black-and-white silent films captivated everyone’s attention. Lepsius purchased a camera, which he used to document the activities of his mission. He knew how to raise funds: they organized expos and photo exhibitions. At the time, caring for one orphan cost 150 marks annually, which was a significant amount. It was suggested that this sum could be collectively raised and donated. Lepsius addressed one of the schools in Potsdam with an appeal: ‘Each of you can donate one mark to support the care of an orphan.'”

The Lepsiushaus undertakes significant efforts in the study of genocides and the education of future generations. It organizes exhibitions, presentations, lectures, and discussions attended by former and current diplomats, ambassadors, journalists, scholars, researchers, and others interested in politics. The staff of the Lepsius House are now initiating the publication of a critical work that will examine all of Lepsius’s writings and address numerous questions: where he gathered his information, how he classified it, and what sources he relied upon.

The Lepsiushaus in Germany collaborates with the Military History Institute of the University of Potsdam and the University of Erlangen. Officially, the Lepsiushaus operates as an association and receives its modest primary funding from the city of Potsdam and the state of Brandenburg. The association also works with the Genocide Museum in Armenia and the Institute of Armenian Studies at Yerevan State University, with which it undertakes joint projects.

In recent years, particularly since 2020, the Lepsiushaus has established direct collaboration with Armenia’s Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Sports (MoESCS). Additionally, there is a project involving the Ministry of Education of Brandenburg. The Lepsiushaus has also hosted official visits from Armenia, including those by MoESCS ministers and parliamentary representatives.

Author: Alexander Martirosyan

All quotes are by Hayk Martirosyan, a researcher at Lepsiushaus.